Gender Inclusiveness in Public Restrooms

Key contributions:

- Secondary research through in-depth review of literature, practice and policy examples.

- Primary research through interviews, visits to gallaries and existing Gender-Neutral Toilets.

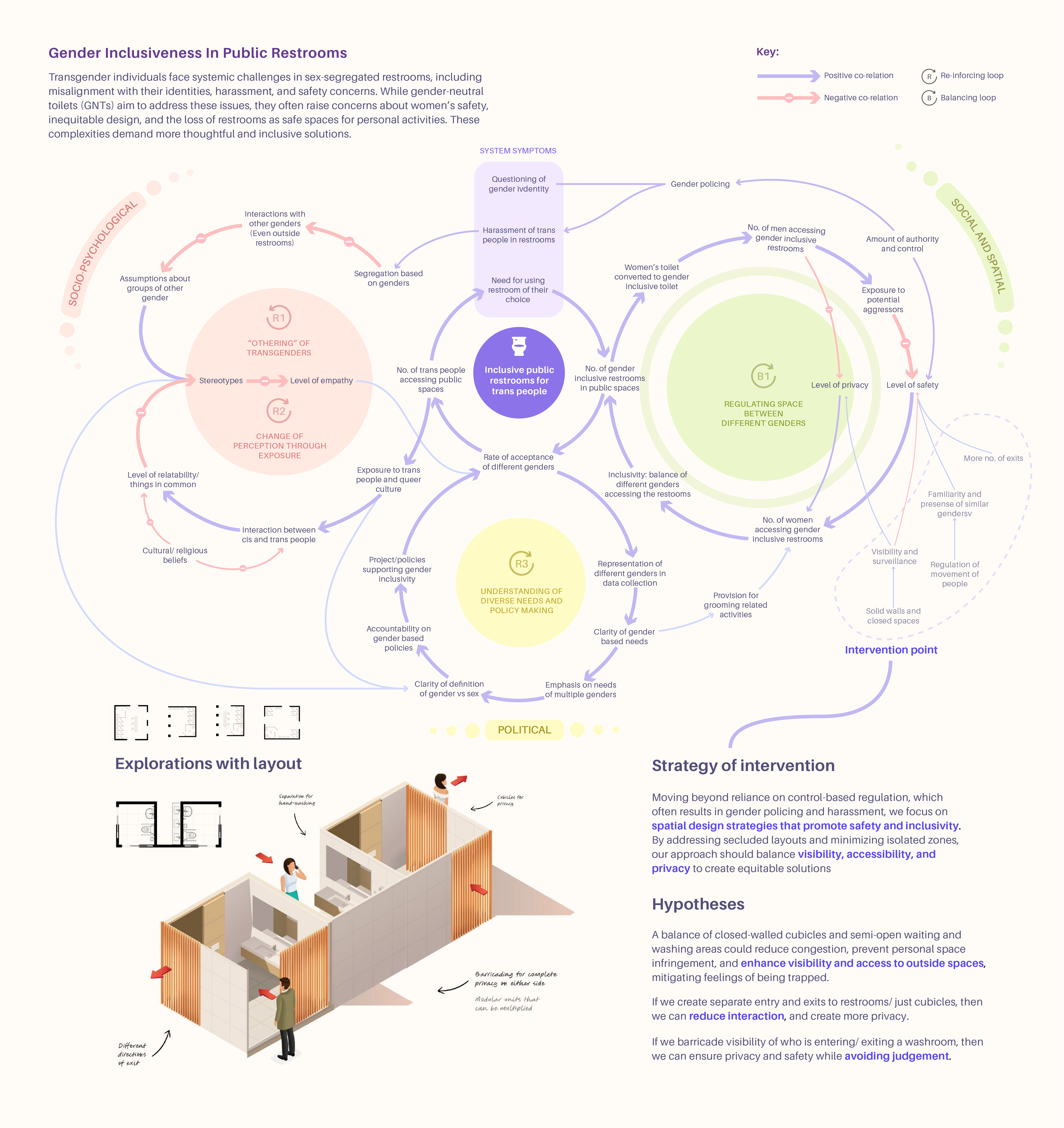

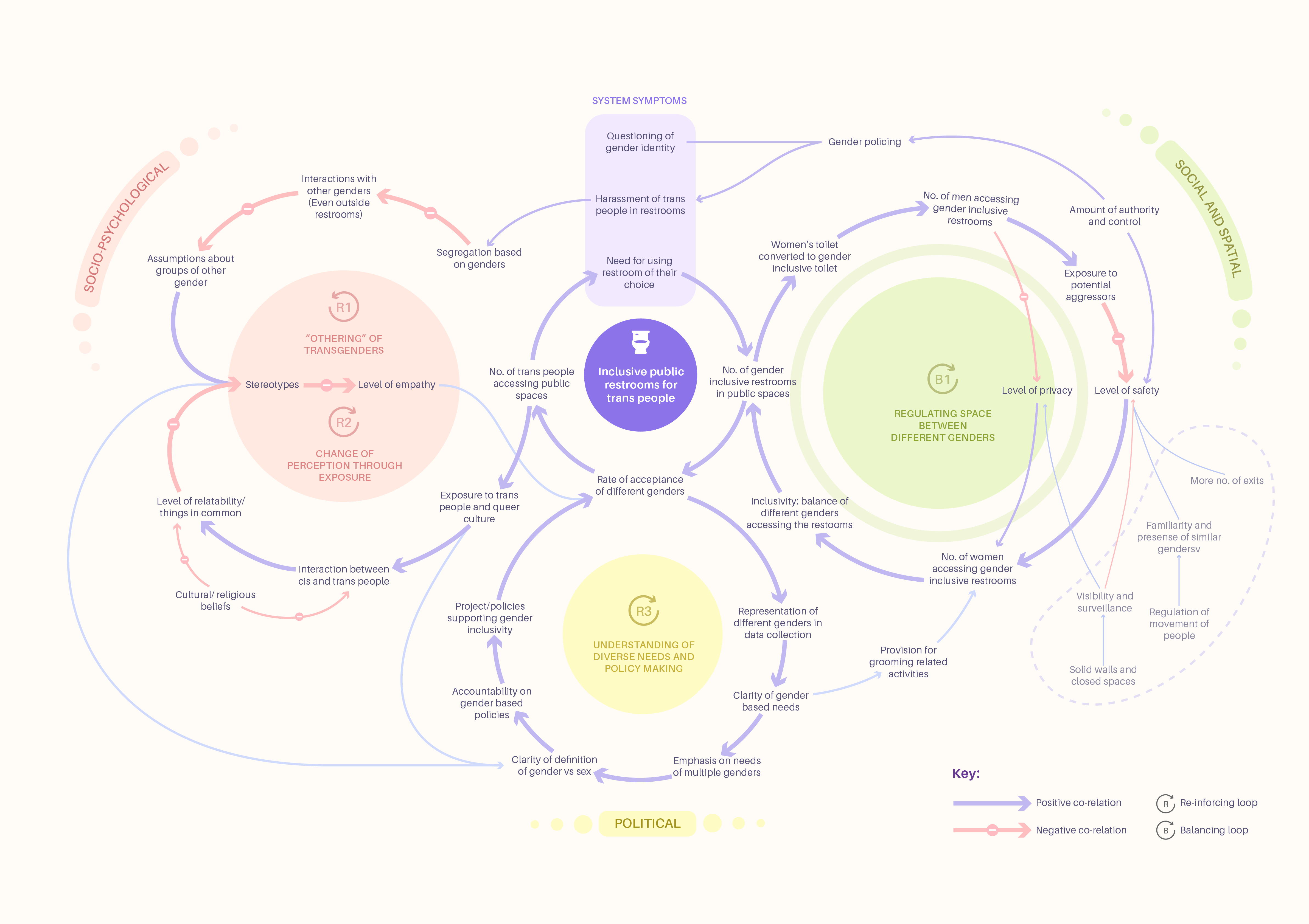

- Created a complex systems map to identify intervention points for moving the system.

- Ideated and prototyped hypotheses for change and ripples-effects in the system.

Background

What is the problem?

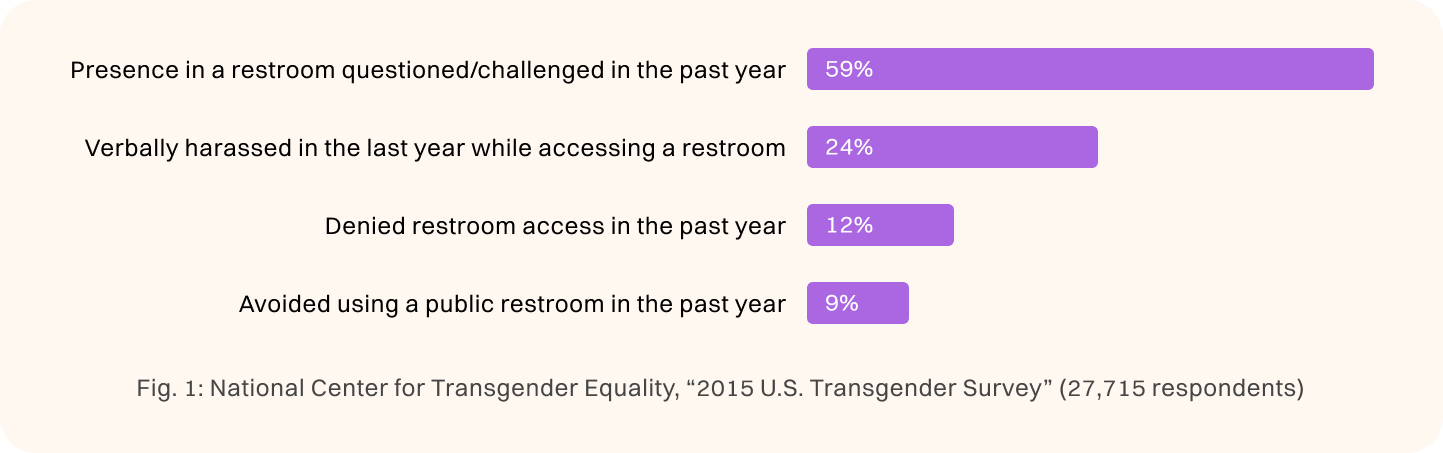

In a system of sex-segregated restrooms, transgender individuals face systemic barriers that deny them access to basic amenities. The key issues include:

Misalignment with Gender Identity: Binary restroom options (male or female) fail to accommodate non-binary and transgender identities, leading to confusion and distress regarding which facility to use.

Harassment and Policing: Transgender individuals often experience scrutiny, verbal abuse, or even physical harassment when attempting to use restrooms aligned with their gender identity, especially if their appearance does not conform to societal expectations.

Safety Concerns and Misuse Perception: Concerns are raised about cisgender men pretending to be transwomen to gain access to women's restrooms, amplifying fears about the safety and privacy of women, although evidence supporting this misuse remains limited.

What is the context?

This issue pertains to any publicly available restroom. However, for the scope of our study, we focus on larger restaurants and pubs (that have space for more than a single occupancy cubicle) as they are places where the need to use a restroom is unavoidable. These are social spaces with a diverse crowd who access restrooms for essential needs and activities like washing hands, freshening up, or grooming. The social nature of these spaces means restrooms are used by individuals and groups, increasing the potential for both positive interactions and conflict or discomfort in shared facilities.

Current System

We examined the system by interviewing three non-binary and queer individuals, visiting the Queer Britain Museum and Wellcome Collection to observe their gender-neutral restrooms, and studying queer culture and restroom-related archives.

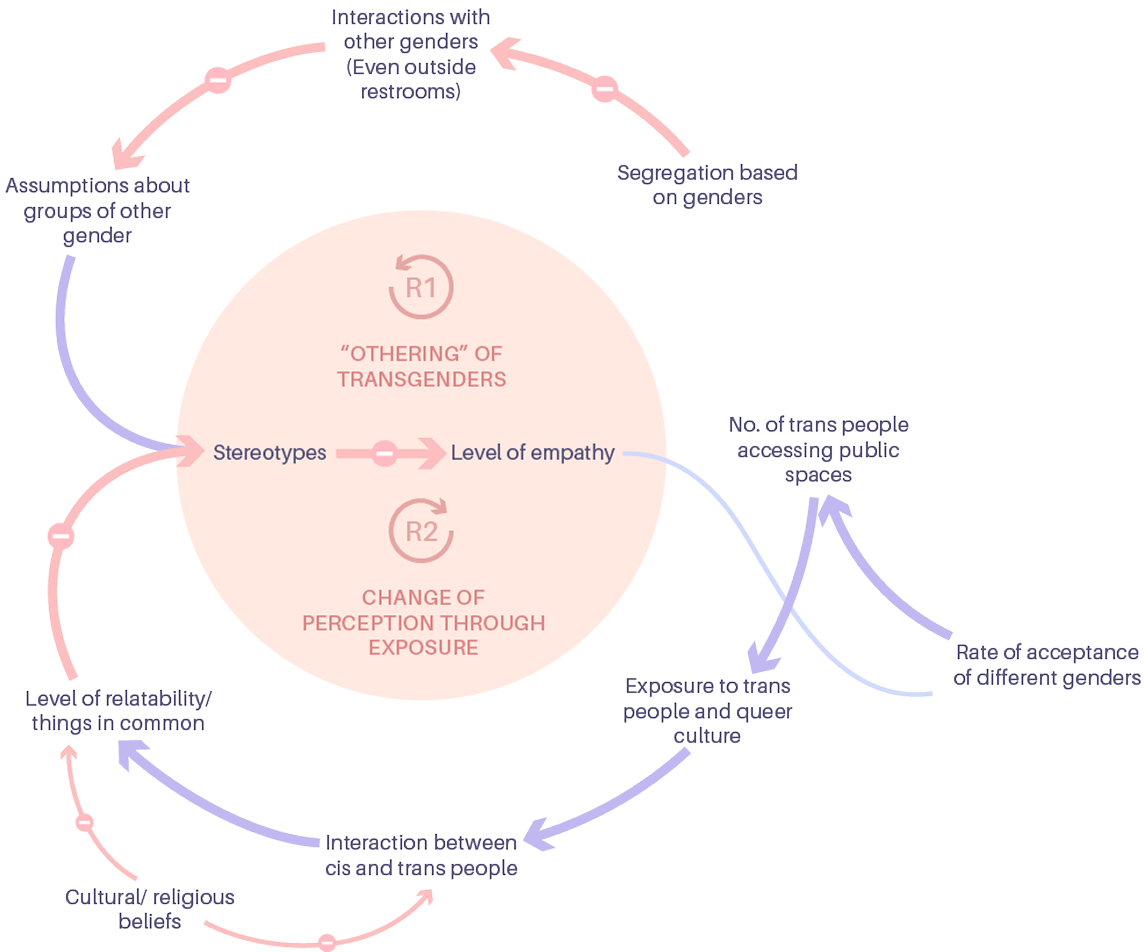

Social and Psychological “Othering” of Transgender People:

Gillig & Bighash (2023) explored how exposure to all-gender cues, compared to gender-segregated cues, led to more positive attitudes toward transgender and nonbinary people.

Change of Perception Through Exposure and Cultural Bias:

The "contact hypothesis" (Allport, 1954) suggests that meaningful interaction with marginalized groups decreases prejudice. Our interview participants shared that in places like Thailand and Hackney, East London—where transgender individuals are more visible—they felt less judged and more accepted. However, a major balancing factor here is existing cultural bias as well as the quality of interaction that can dilute or reinforce stereotypes.

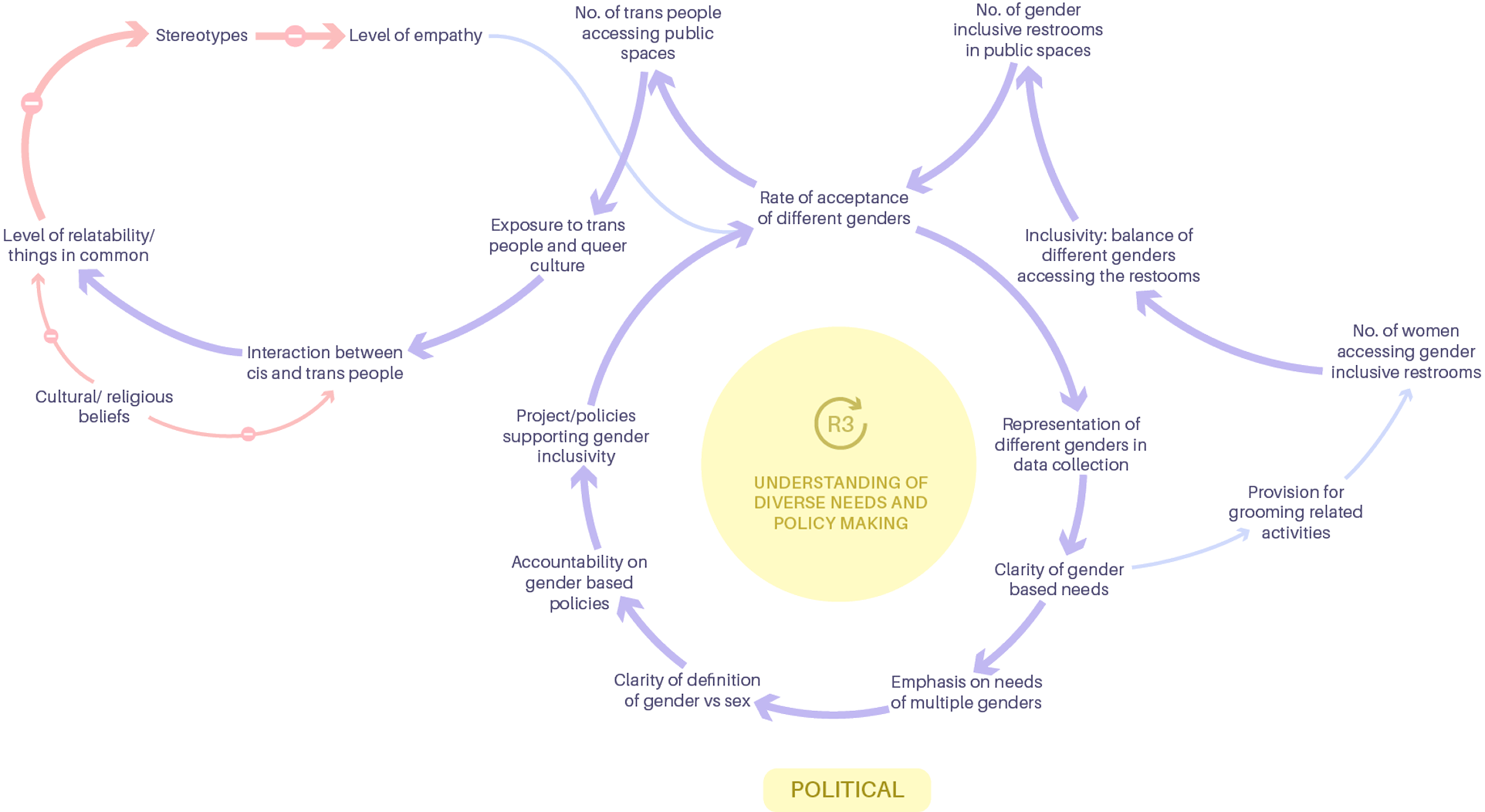

Understanding Diverse Needs in Policy-Making:

A clear understanding of the difference between biological sex and gender is also required to address the needs of transgender individuals (Robinson et al., 2024) Research by Peterson (2018) highlights how empirical data on restroom use, rather than stereotypes, can inform design— for example, understanding the need for personal grooming for women and queer people and designing provisions with privacy in mind.

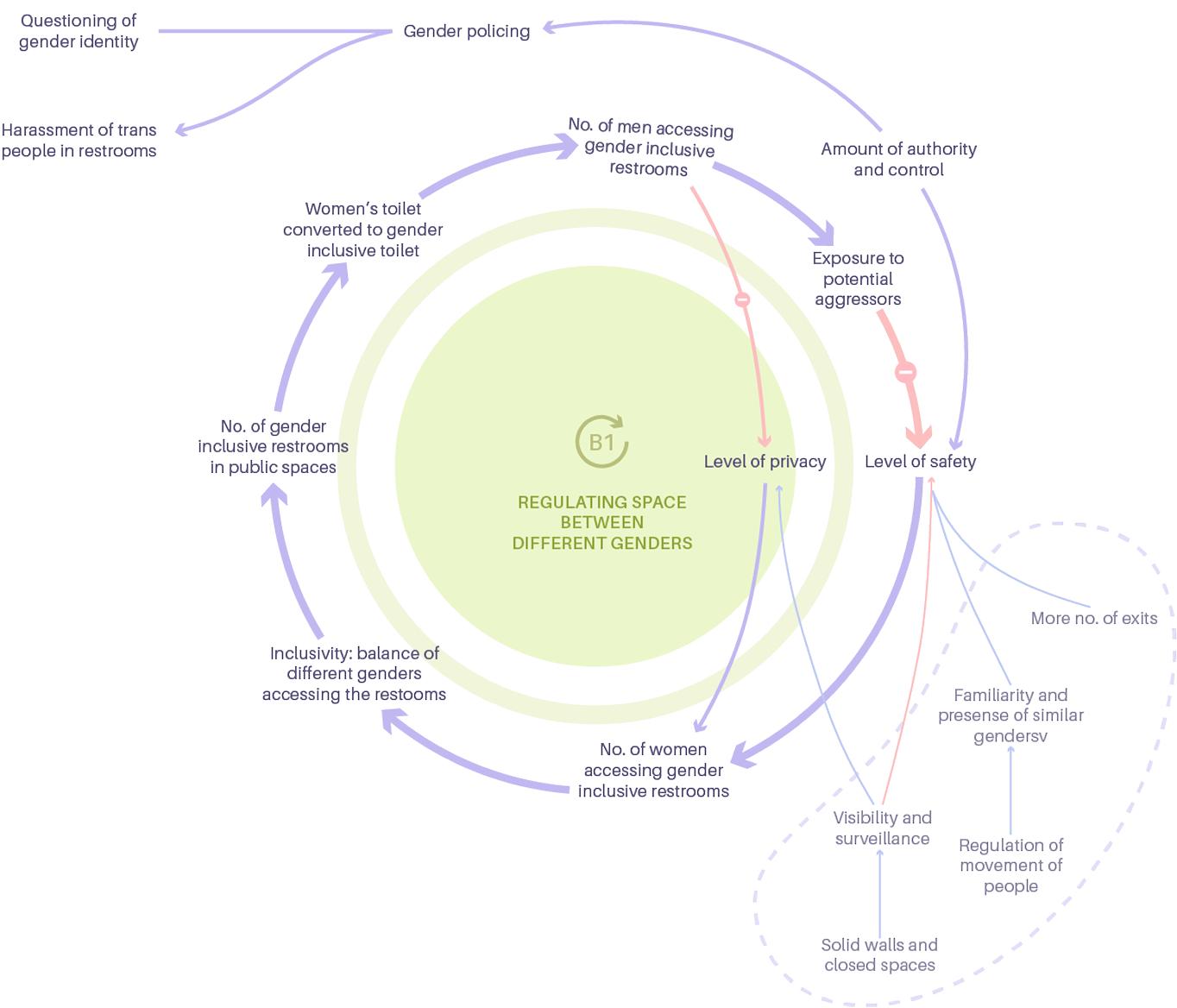

Regulating Space Between Genders:

LEVERAGE POINTConcerns about women’s safety when sharing restrooms with other genders remain the most commonly cited reason for opposition to gender-neutral toilets. This is especially critical in restaurants and pubs, where diverse crowds and the presence of alcohol heighten safety concerns. Hence, our intervention point lies here, addressing key concerns on the ground.

We realized that even sex segregation does not entirely solve safety concerns, as aggressors can still trespass. What ensures safety is regulation, often through control and authority. However, this control can lead to gender policing and verbal harassment of transgender individuals.

Restrooms often have secluded layouts, with cubicles creating isolated zones that can enable unnoticed misconduct. Thus, we aim to create an inclusive yet naturally regulated space for better safety and privacy of all users.

How might we create a gender-neutral yet naturally regulated space for better safety and privacy of all restroom users in a restaurant?

Hypotheses of intervention

Our Vision

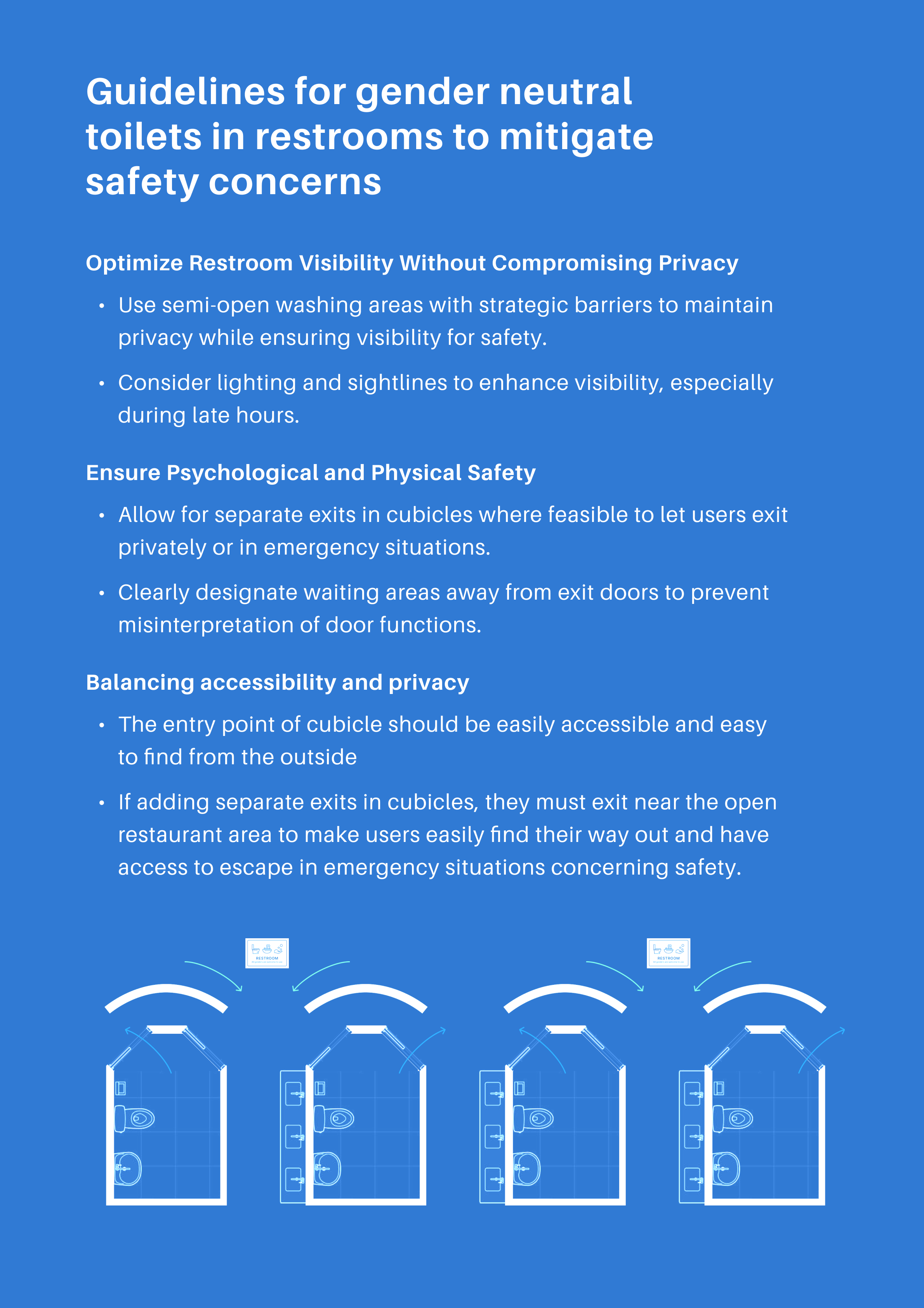

We envision public restrooms as inclusive, accessible, and naturally regulated spaces where individuals of all genders, including transgender and non-binary people, feel safe and comfortable. Moving beyond reliance on control-based regulation, which often results in gender policing and harassment, we focus on spatial design strategies that promote safety and inclusivity. By addressing secluded layouts and minimizing isolated zones, our approach should balance visibility, accessibility, and privacy to create equitable solutions that respect diverse needs while mitigating safety apprehensions.

Inference 1

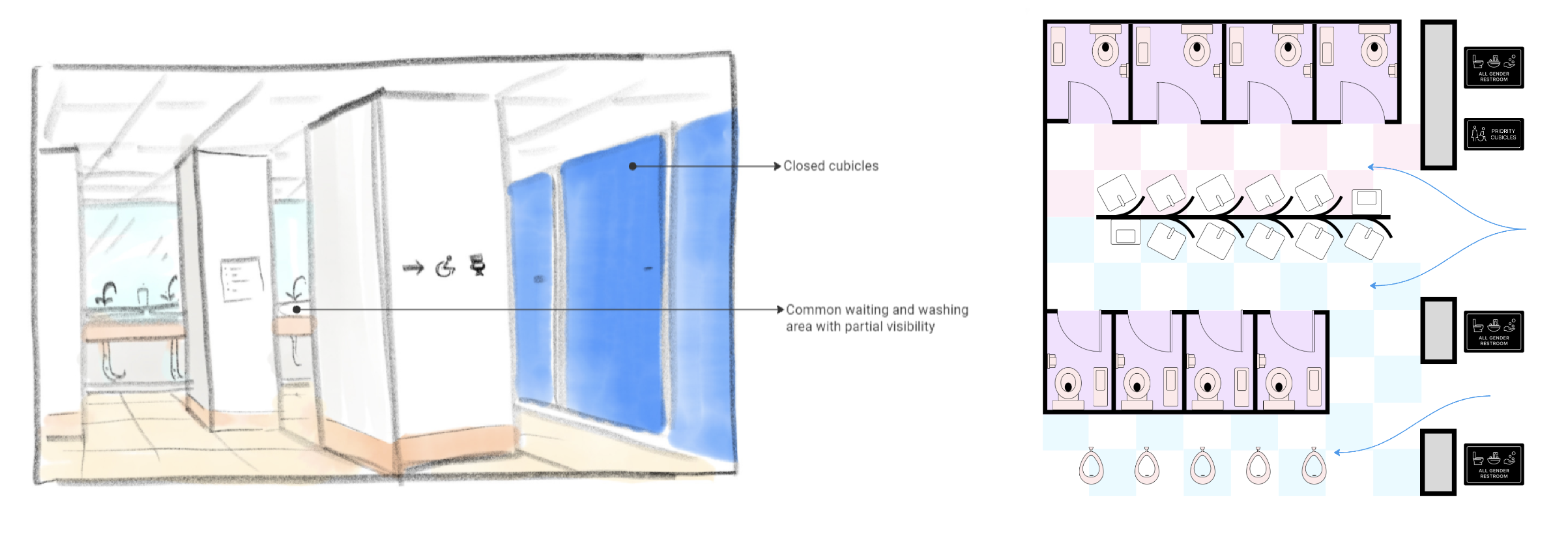

Washing zones are common areas frequently used in pubs and restaurants. Women and transgender/non-binary people often use these spaces for grooming activities. When these areas are closed-off and secluded outside of common cubicles, they can compromise safety.

Hypothesis 1

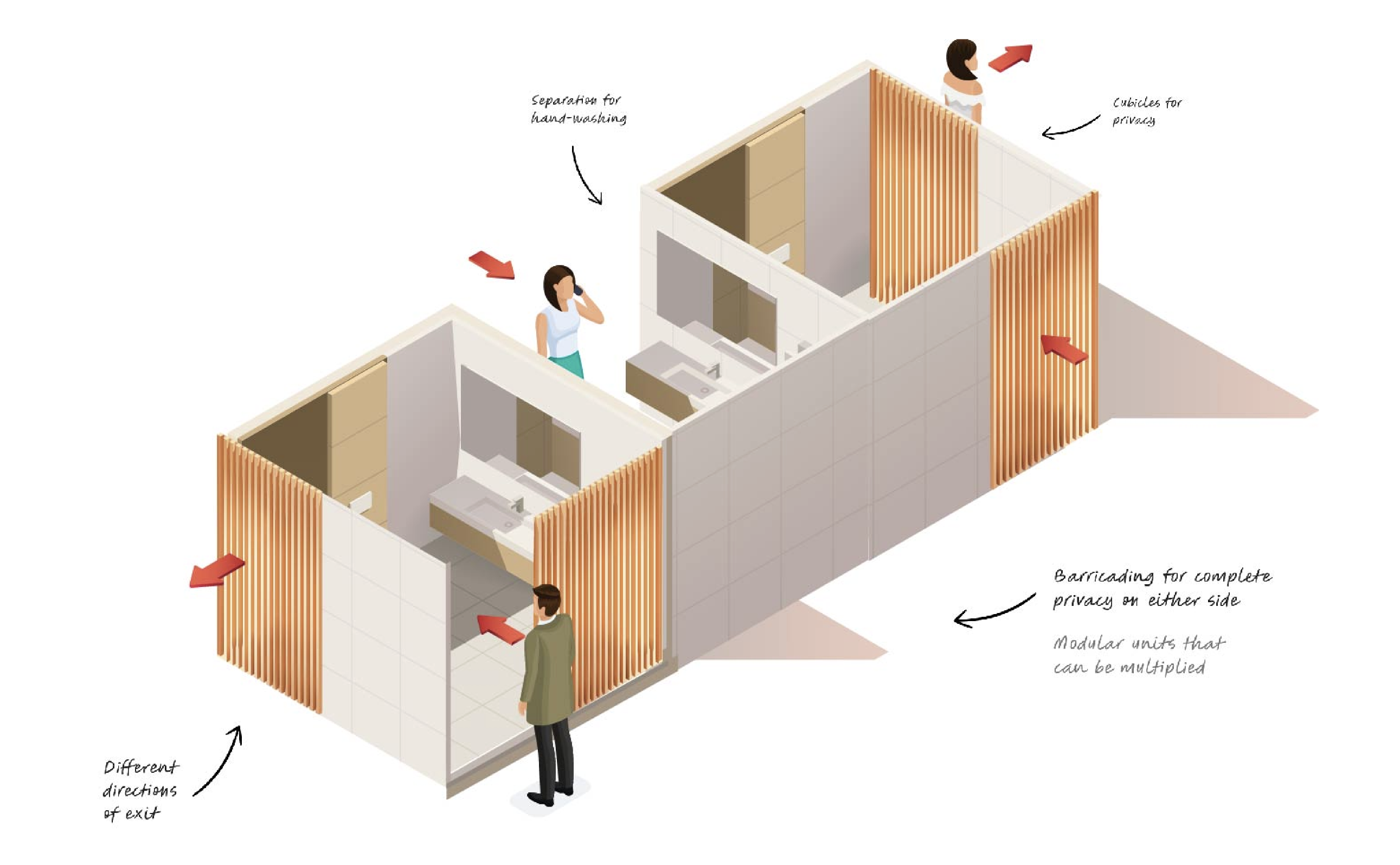

A balance of closed-walled cubicles and semi-open waiting and washing areas could reduce congestion, prevent personal space infringement, and enhance visibility and access to outside spaces, mitigating feelings of being trapped.

Inference 2

Restrooms often have secluded layouts, with cubicles creating isolated zones that can facilitate unnoticed misconduct.

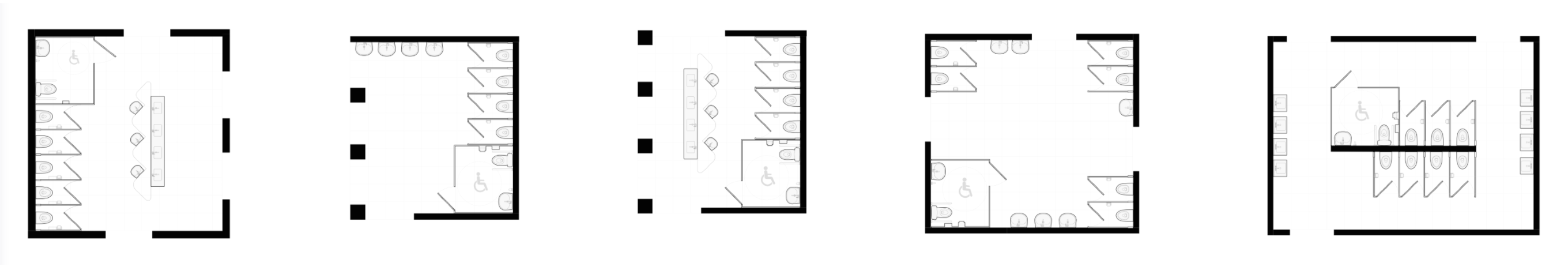

Hypothesis 2

If we create a separate entry and exit to restrooms/ just cubicles, then we can reduce interaction, and create more privacy.

Inference 3

Long queues in front of cubicles and visibility of who is using them often becomes a signifier for the gender of the washroom, often leading to policing or reduced perception of privacy.

Hypothesis 3

If we barricade visibility of who is entering/ exiting a washroom, then we can ensure privacy and safety while avoiding judgement.

Prototype and Testing

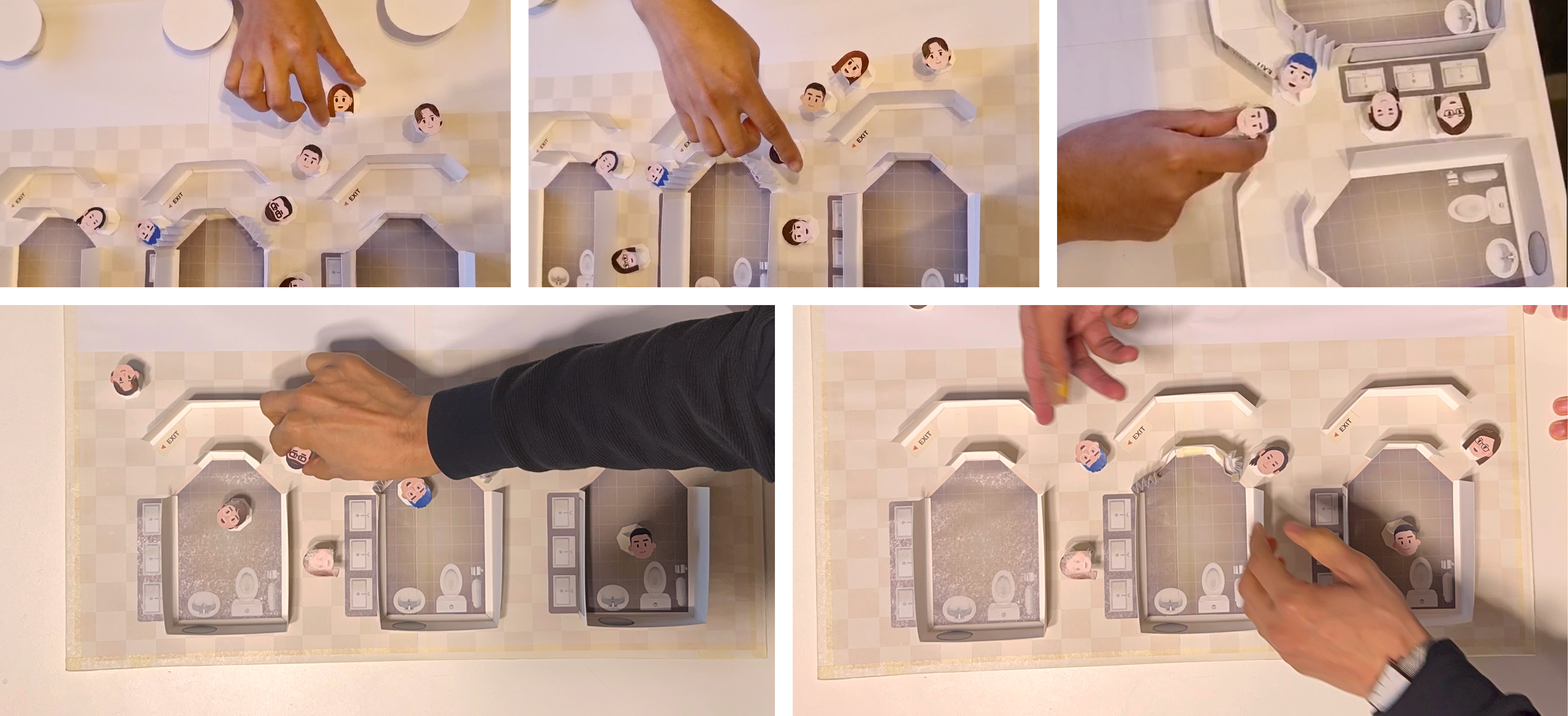

To test out our different strategies, we build a 3D model to understand and analyse navigation around proposed spatial arrangements and how people interact and behave.

Areas to observe:

- Choice of where to go based on people

- Effect of barricading and having private exit

- Understanding of entering and exiting the cubicle

- Effect of visibility into separate washing area

Learnings and insights

Choice of restroom: 1/2 females and 2/2 males mentioned the person (and their gender) last using the restroom may not matter, they’ll prefer the closest cubicle or the one visible first from their location. 1/2 females mentioned If a man has gone first and its western commode, I may not prefer that.

Separate entry and exit: For first-time users, it was not always clear that there are separate entry and exit just from signage. As there were characters standing in queue near entry, in our setup, people went to the exit doors thinking they were different cubicles.

Safety and privacy: Participants mentioned depending on the crowd outside and their mood, they might want to exit separately and privately but might be anxious if the two doors are locked or not and if anyone is standing at the exit.

Open washing area and visibility: All participants did mention that having a semi-open washing area and better visibility from outside near the entry and exit of cubicles with some barricade can mitigate safety concerns but time of day, lighting, etc. will be important too.

Thank You!

-

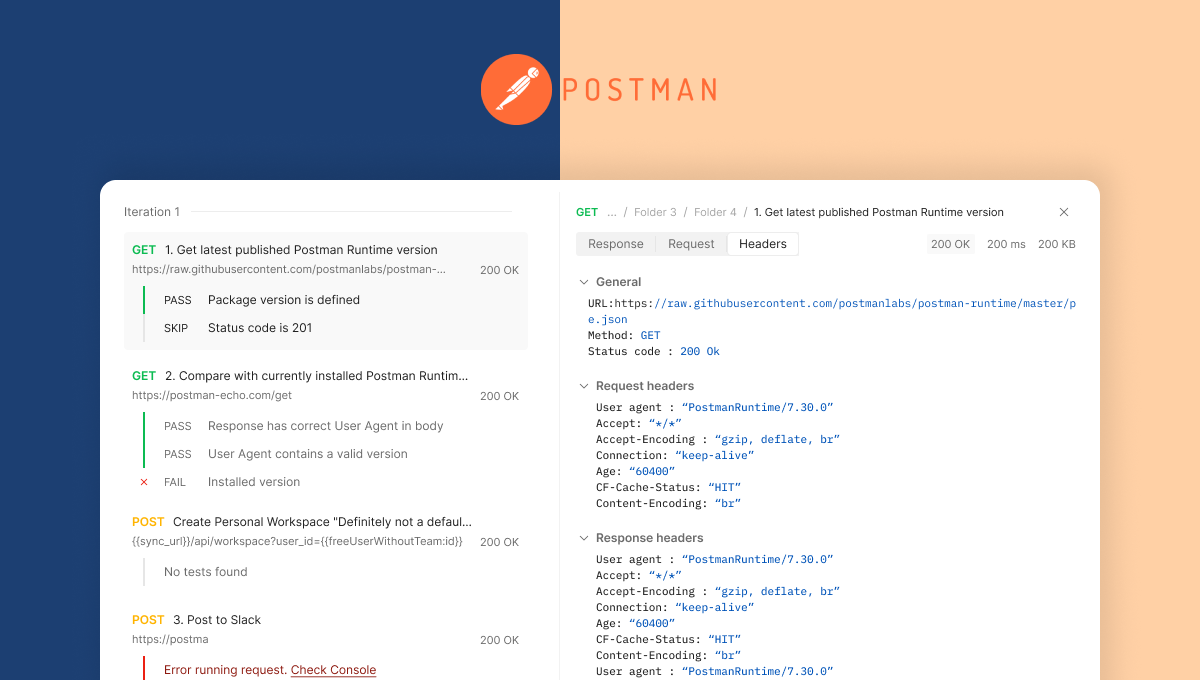

Improved debugging flow

Led the problem discovery, journey mapping and design of the debugging flow for API tests in Postman.

-

Accessible error signifier

A small change big impact story of creating subtle yet effective error signifiers and reducing the error.

-

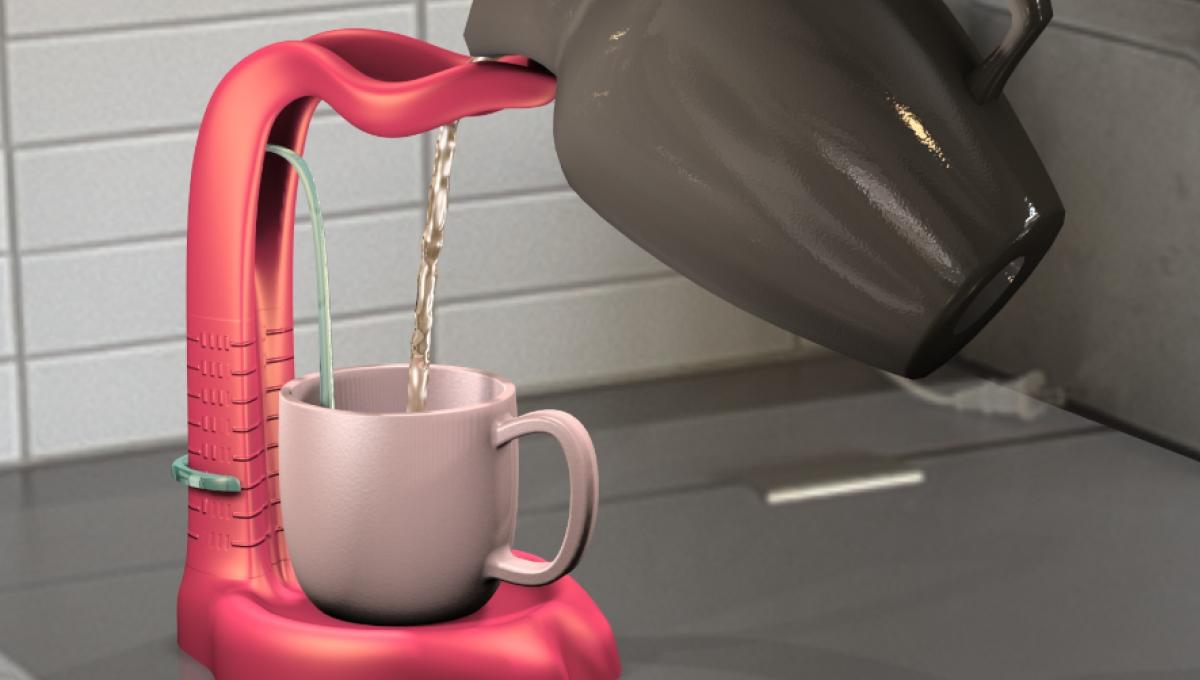

Assistive device to pour

A device that helps visually impaired users safely pour hot liquids by communicating with its form.